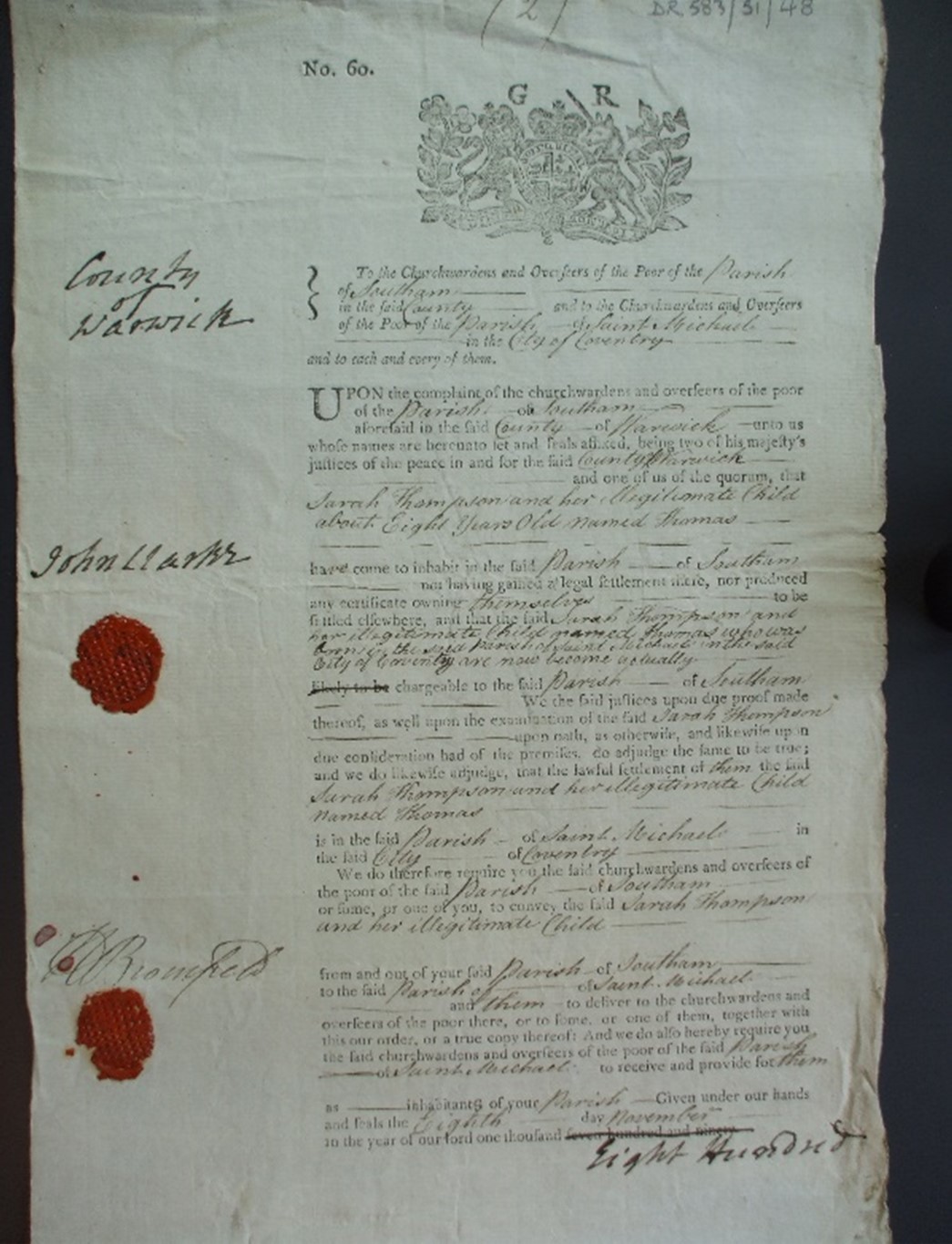

Removal order for Sarah Thompson and her child, to be returned to Southam … Ref: WCRO: DR 583/31/48; 8/11/1800

In October 1782 a constable from Birmingham apprehended an itinerant, Richard Fairfax, who had, ‘ … been lying in the open air … unable to give a good account of himself … ’. On examination under oath, it was established that Richard was a vagrant who had travelled illegally from the parish of Southam and, as such, was expelled and returned there. In the same year John Cowley, apprehended on a charge of begging in the parish of Handsworth and earlier in the year found begging in the borough of Walsall, was charged with vagrancy on both occasions and sent back to Southam under settlement removal orders.

Over hundreds of years the question of vagrancy and the costs involved in supporting individuals and families through ‘parish relief’ (rates) had become a real financial issue for most parishes in the country. The problem was exacerbated after the 1601 Poor Law Act, as legally each parish could administer their own ‘rate’ and the amount of ‘relief’ to be given. This led to people exploiting the legislation by moving to what they considered to be more generous parishes.

To redress this trend, the Settlement Act 1662 determined that every person had their own ‘parish of settlement’ (usually the parish of their birth). Thus, local justices of the peace could investigate and examine, under oath, any individual who was suspected of being a vagrant from a different parish. If the case was proved, the individual or family was removed by the local constable back to their legal settlement.

On 8 November 1800 Sarah Thompson, with her son Thomas, aged eight, was suspected of having, ‘ … intruded upon the parish of Southam, from the parish of St Michael’s in Coventry … ’, claiming ‘outdoor relief’. As the settlement of both mother and child was St Michael’s parish the local constable conveyed them to the overseers of the poor there.

It is evident from existing records that many individuals from Southam found their way across the country at this time. In 1782 Elias Wright, found begging in St Bride’s, London, confessed that he had lived for two years as a yearly hired servant of William Bud, a farmer from Southam. However, he had failed to obtain a settlement order after leaving the area, so he was returned there. In 1787 Elias was again apprehended begging in St James’s, Westminster, by the constable Thomas Edwards, and subsequently returned to Southam.

Another sad case in 1779 involved Elizabeth English and her five children, who were found begging in Northampton. The local constable charged them with being ‘ … rogues and vagabonds … wandering and begging in the town … ’. Their fate was sealed under examination, and they were returned to Southam under escort. In 1797 the same outcome befell Mary Morris, who was apprehended by the constable Thomas Lawrence in the City of London. She was charged with being a rogue and vagabond, but committed to Brideswell Hospital for seven days as punishment before her long journey home began.

It wasn’t until the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act and the creation of workhouses that a real nationwide initiative was introduced attempting to address the issues involved.

Dr Raffell’s new book about Southam’s Workhouse is available from the Southam Heritage Collection, price £7.

Southam Heritage Collection is located in the atrium of Tithe Place opposite the Library entrance. Opening times Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday mornings from 10am to 12 noon. To find out more about Southam’s history, visit our website www.southamheritage.org telephone 01926 613503 or email southamheritage@hotmail.com You can also follow us on Facebook.

Leave A Comment