In the early part of 1765 in Southam, a series of tragedies involving the deaths of many people affected the town. The majority of these were from the workhouse, the institution established in the 1740s in support of the poor and destitute. Early victims included Mr and Mrs Malens, William Gibbs, Ann Rainbow, William Pettifer and his wife Mary, and other members of the Rainbow and Middleton families. The Church records show that these people and other families had been held in isolation under the care of several nurses, following an outbreak of smallpox.

One of the most feared diseases in the country since the Black Death in 1348, smallpox was virulent and contagious. The symptoms started with a fever and vomiting, followed by the formation of ulcers and rashes on the skin which soon blistered and scabbed, resulting in scarring, disfigurement and, for many, death.

In Southam it was particularly prevalent from the 1760s, usually affecting the elderly and frail, who often lived in poor conditions with primitive drainage, a contaminated water supply and filthy outdoor privies. Although efforts were made to understand and combat outbreaks of the disease locally, including an attempt by a Dr Snow to inoculate the whole town in 1778, at a cost to the parish of £20, cases continued. Dr Snow’s initiative had little medical foundation, with no aftercare, analysis or records of effectiveness.

We know that Mary Pettifer was nursed by a Mary Orton, but nevertheless died in September 1765. In the same month the deaths of Edward Harris, the Master of the workhouse and his wife, and of other inmates including Ann Horton and Edward Lee, soon followed. In the October, William Averns, Henry Brown, Elizabeth Higham and others became victims. The doctor’s bill in caring for these poor individuals came to £4 2s 2d.

In 1766 a Dr Arnold attempted to help by purchasing ‘6 loads of hame (ham) for the poor’, at a cost of £4 10s, to ensure that the sufferers had adequate protein nourishment in fighting the infection.

In the ensuing years the death rate declined, although provision through the Poor Rate of food, clothes and nursing care was still needed for families affected by smallpox. Alas, in 1774, William Daniel, apothecary, landowner and owner of the workhouse building died, leaving in his will a contribution to continue supporting those in need. Such was his standing as a charitable individual that the poor of the town formed a procession following his coffin as a tribute to him.

Another Master of the workhouse, Simon Turner, passed away in 1773, followed in 1778 by his replacement, John Edwards, along with six other families, including the Griffins, Hills and Tomes.

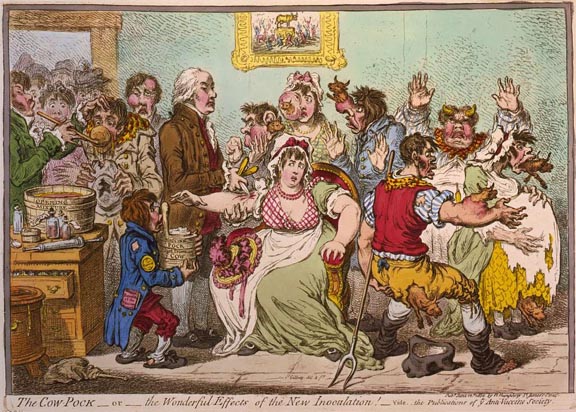

A cartoonist’s satirical view of how the cowpox vaccination would affect the population

It wasn’t until the late 1790s that the disease was finally brought under some control by a vaccine developed through the work of Edward Jenner in 1796. Around this time it was discovered that smallpox could be effectively controlled by exposure to a vaccine adapted from a strain of ‘cowpox’, a much milder disease causing lesions on the hands and arms, commonly experienced by milkmaids who had been working with infected cattle. These workers were found to be immune to smallpox.

The story does not end there. Despite vaccinations, smallpox was still prevalent in 1874 when, of the 821,856 children born in England and Wales, nearly 80,000 died of smallpox before they could be vaccinated. Of the rest, 94% were successfully treated through vaccination.

Southam Heritage Collection is located in the atrium of Tithe Place opposite the Library entrance. Opening times Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday mornings from 10am to 12 noon. To find out more about Southam’s history, visit our website www.southamheritage.org telephone 01926 613503 or email southamheritage@hotmail.com You can also follow us on Facebook.

Leave A Comment