In 1530 the government of Henry VIII passed into law an Act designed to deter vagrants from roaming from parish to parish. Any individuals considered as such could be apprehended and carried into town:

‘ … tied to the end of a cart naked, and beaten with whips … till the body shall be bloody by reason of such whippings.’

In the reign of Elizabeth I a ‘whipping post’ was substituted for the cart. Southam had such a post attached to the town’s stocks, situated at the junction between Pendicke Street and Daventry Road. Its use is well documented; the parish churchwardens’ notices in 1714 record that 1s 4d was paid:

‘ … for sending a Ballet-Singer away … and whipping.’

One wonders how such vicious measures arose.

From mediaeval times there was no support for the poor in England apart from the charity distributed by churches, abbeys and monasteries. This was ended by the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII in 1538.

Various laws had been passed to address the problems of poverty, including the Ordinance and Statute of Labourers Acts in 1349 and 1351 which merely criminalised those who were poor and unemployed. The prevailing attitude reflected in the legislation was bleak, to the point that citizens helping the poor could be imprisoned themselves through their own kindness:

‘ … as long as they (the unemployed) live by begging, do refuse to labour, giving themselves to idleness and vice, and sometimes to theft … none upon the said pain of imprisonment … give anything to such … ’

In 1388 under the Statute of Cambridge the law changed to provide that:

‘ … the needy who are incapable of labouring are permitted to beg for alms, but only in their own community.’

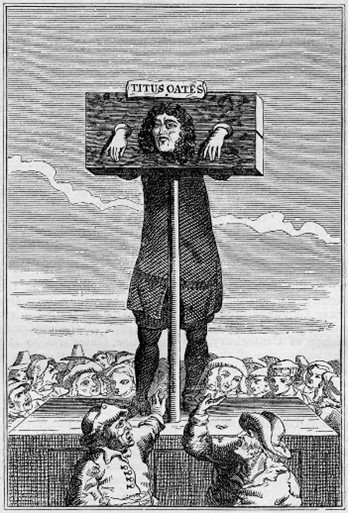

Over time, further legislation attempted to deter beggars by such means as branding, stigmatisation through emblems sewn onto clothes, the creation of Houses of Correction and punitive measures such as stocks, the pillory and whipping. Nevertheless, the plight of the poor and destitute continued and their poverty was often associated with crime.

Records from both the town’s churchwardens’ accounts and notices, and from the Justices of the Peace Petty and Quarter Sessions, help us to appreciate how Southam was affected, particularly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. In 1661, Thomas Goode of Southam was fined for ‘ … harbouring rogues and vagabonds contrary to the statute … ’

In 1667 Stephen Burnett was indicted for stealing: ‘ … four pewter dishes of the value of 8d of the goods of Edward Newell.’ His sentence was ‘ … to be flogged at Warwick and then at Southam.’

In the same year Mary Higham was indicted for stealing a smock to the value of 10d; she confessed and was whipped.

There is no real evidence to show the extent to which such offences were motivated by poverty, but vagrancy was itself treated as an offence. In 1711 4d expenses were paid: ‘ … for searching town for vagrants;’ and in 1723:

‘ … paid a charge for watching two vagrants and lodging them and locking them up after they ran away: 5s 2d.’

In 1777 the parish faced charges of £8 12s 6d in expenses:

‘ … in taking up six vagrants and sending them to prison, two men and two women to Coventry Jail and two men to Warwick Jail.’

These are but snapshots of the measures taken in the town’s history, which were typical of parishes throughout the country and prioritised the issue of costs. By law, itinerants should only have been the responsibility of their birth parish (their ‘settlement parish’). If apprehended they would have been escorted ‘home’ after an appropriate punishment, transferring the costs to ratepayers elsewhere.

Southam Heritage Collection is located in the atrium of Tithe Place opposite the Library entrance. We are open on Tuesday, Thursday, Friday and Saturday mornings from 10am to 12 noon. To find out more about Southam’s history, visit our website www.southamheritage.org telephone 01926 613503 or email southamheritage@hotmail.com You can also follow us on Facebook.

Leave A Comment