The name ‘Smith’ originates from the old English word ’smythe’ meaning ‘to strike’ and is a person who works with any metal – ‘blacksmith’ being one who works in iron and steel. The ‘black’ refers to the black layers of oxides on the surface of iron during heating. A Blacksmith is the skilled occupation of making and repairing iron tools and implements, and includes the specialist skill of shoeing horses; the farrier.

From mediaeval days, Southam was at the hub of the criss-crossing drovers’ roads from Wales to London and as well as shoeing horses for the long trek, they would sometimes have to shoe cattle as well. Prior to the railways, Southam was on the main northern roads to and from London both for the travellers and post-coaches as well as the carriers and carts. This provided more than enough blacksmith and farrier’s work for many men in the town.

Each village around Southam supported a blacksmith who was a farrier as well, and the old blacksmith’s forges can often be spotted in a village by a lane or house name. Where there is a green with a horse chestnut tree this often indicates the location of an old forge. Horses waiting to be shod were tied in the shade of the tree on the grass. In 1842 this was the inspiration for Longfellow’s famous poem ‘The Village Blacksmith’, many of you will be familiar with the opening lines: “Under the spreading chestnut tree / The village smithy stands”.

In Southam, apart from the journeymen blacksmiths around the town, there are two main Smithys marked on the 19th Century maps. John Claridge, a master blacksmith with apprentices, was in Pendicke Street and ideally situated for the passing drovers using the Welsh Roads. The Wagstaff family forge was in Coventry Street opposite The Grange and was well placed for the Beast Market in lower Coventry Street. Henry Wagstaff had come to Southam from Newbold Pacey in early 1800. As sons often follow their father’s trade, it is possible that his father was also a blacksmith, and certainly his own son William and grandson Francis both became blacksmiths and farriers in Southam.

Horses have played an important role in the history of man. As early as 100BC horseshoes were developed, and became linked with folklore and superstition, good and bad luck and fairies, witches and the devil. Iron was deemed magical as it withstood fire, and the seven nails used to fix a horseshoe is said to be a lucky number. In the 10th Century, legend has it that St Dunstan (a blacksmith) was visited by the devil, who asked to be shod. Dunstan nailed a hot shoe to his hooves, the devil howled with pain and Dunstan chained him up, refusing to release him until he promised to never enter a house that had a horseshoe nailed over the doorway. St Dunstan became the Archbishop of Canterbury in 959AD.

So all that remains, is for you to decide, do you hang your horseshoe with the points up to stop the luck falling out, or do you nail it a little to one side or upside down so that a little, or a lot of the luck falls out onto those passing underneath?

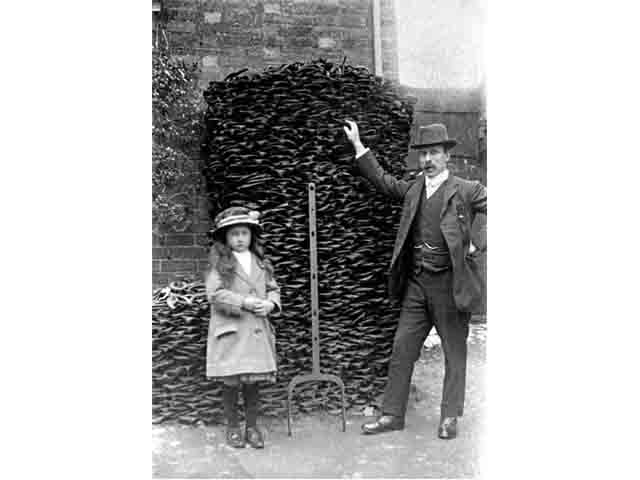

The photograph shows a mound of used horse shoes, with Dolly (Dorothy) George and her father, Southam blacksmith Leonard George. Dolly married William Hill in 1939 and they all lived in Pendicke Street, near to where the Clinic is now.

By Linda Doyle

Hand painted ‘lucky’ horseshoes are just one of the items we sell to raise funds to help preserve and promote Southam’s history. If you are interested in finding out more about local history, contact Southam Heritage Collection. Please see our website for where to find us and our current opening times. Contact: 01926 613503 email southamheritage@hotmail.com visit our website www.southamheritage.org and find us on Facebook: Southam Heritage Collection.

Leave A Comment