For over a thousand years Southam has existed as a cross roads market town which can be exited in eight directions. Two made up an historic drove road for the cross country movement of livestock; four made up two stage coach routes and the others routes join Southam to Rugby and Kineton.

In that millennium Southam gained a 10th century Holy Well, a 13th century market, a 14th century church, a 16th century royal mint, was mentioned twice in a Shakespeare play and in the 18th century the first public dispensary in the land was established. It was also home, in no particular historic order, to water and windmills, at least two abattoirs, a tannery, a workhouse, a gas works, a Catholic convent, three non-conformist chapels, fourteen or more pubs, a livestock market, blacksmiths, ironmongers, stone masons, cobblers, tailors and dressmakers, a parish hall, corn and cattle feed merchants, two banks and a Southam Building Society, as well as being a major stagecoach stop!

In living memory there were at least four butchers, three bakers, two milk rounds, a shoe shop, several dress shops, a drapery, a bike shop and endless sweet shops. There was a town band, a dance band, Kayes works band, a drama group, weekly film shows, old time dances, Boy Scouts and Cubs, Girl Guides and Brownies, Air Cadets, Mothers Union, Women’s Institute and Christian Endeavour, to name but only a few!

In the Beginning

At the time of the arrival of the lime and cement industry, Southam was a very self contained town with a population of approximately 1500 folk, with most of working age employed in and around the town.

The cement story probably starts in Southam before the turn of the 19th century and in the very early days there were at least nine small and individually owned lime works around Southam.

One of the earliest lime and cement manufacturers was Richard Greaves of Stratford-on-Avon who inherited land at Southam and Stockton from his father-in-law and was in partnership with J W Kirshaw of Warwick, and near Harbury he established a second lime and cement works. In the 1860s the Greaves partnership was joined by John Bull and became ‘Greaves, Kirshaw & Bull’. Then when Kirshaw retired and in 1870 Greaves died, his nephew Michael Lakin became a partner and the business became ‘Greaves, Bull & Lakin’ and Harbury became their main works.

In 1927 ‘Allied Cement Manufacturers’, makers of ‘Red Triangle Cement’ bought the Harbury works, but went bankrupt in 1931, when ‘Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers’ (APCM) bought them out. Later they became part of the ‘Blue Circle Industries’ and was generally referred to as ‘Blue Circle’ after it’s prominent logo which it employed worldwide and is still seen today on the lorries of ‘Lafarge’, the final (French) owner. Harbury eventually ceased manufacture in 1970 after which it operated as a depot for a while receiving supplies by rail.

At Stockton, one of the earliest lime works and later only a small cement works, was William Griffin’s, but by World War I it had been quarried out and the land sold.

‘Charles Nelson & Co Ltd’ was also operating at Stockton by 1844, first as lime burners, but from about 1860 was manufacturing cement, until near bankruptcy in 1937 when ‘Rugby Portland Cement Co Ltd’ took a share with a full takeover in 1945, after which it was completely closed down in 1949.

From 1854, William Oldham was in partnership with Lawrence Mallory Tatham, a London lime and cement merchant trading with Capt. Arthur Lister-Kaye. In 1868 Oldham retired and the quarries were leased to ‘Tatham, Kaye & Co’ and when Tatham retired, Lister- Kaye continued the business and eventually purchased the works from the Oldham family.

The Southam works on the Long Itchington boundary was ‘Kaye & Co Ltd’ from 1875 to 1934 when receivers were called in and the assets purchased by ‘Rugby Portland Cement Company Ltd’ who were in turn bought out by the ‘Ready Mixed Concrete Group’ (RMC), an Australian company, in 2000, soon after which production at Southam ceased with the New Bilton, Rugby works taking over all manufacture despite all quarried raw materials still coming out of the Southam quarry. The Southam works was finally demolished in 2011.

This all shows the massive impact the arrival of big time cement production must have had on Southam, Harbury, Bishops Itchington, Long Itchington and Stockton!

The Workforce

Barrow Runs

In a short space of time a workforce totalling up to 1000, mostly men, but with a small percentage of ladies, would have been recruited as cement production is a continual process with a kiln only being shut down when absolutely necessary, usually for the internal re-fire bricking.

This made three-shift manning the norm with day work maintenance gangs of fitters, electricians, stores staff and a yard gang who mopped everything else up. There were also quarrymen, loco men, packers and delivery drivers.

To house employees nearer to their work, villages were built at Deppers Bridge by Blue Circle and Model Village by Rugby (Kayes), while many houses were built by both Greaves and Nelsons at Stockton.

Looking After the Workforce

First hand knowledge of life at Stockton has disappeared, but it is worth commenting on the “chalk from cheese” philosophies variously displayed by ‘Rugby Cement Co’ and ‘Blue Circle’.

The former was run by an extremely accomplished accountant Chairman, Sir Halford Reddish who improved profits on a year by year basis over a long career at their Crown House headquarters in Rugby, although adding nothing unessential to the running of the works.

‘Blue Circle’ would also have a children’s Christmas party in the Bishops Itchington Memorial Hall and a trip to the Coventry Hippodrome Pantomime. There was an excellent works canteen which included a hot cooked dinner service at 2 shillings per head. There was also a regular Company magazine which highlighted progress and activities at other plants in this huge worldwide organisation.

The cement industry must have sucked all of the fittest out of their previous occupations, in service, trade and on the local farms as the work was virtually guaranteed for one’s working life and better paid. On the other side of the coin it could be extremely hot, cold, dirty and at times dangerous.

Up until the 1960’s most of the employees either walked or cycled to work and only then did car ownership start to appear along with staff from further afield.

Canal, Rail and Road

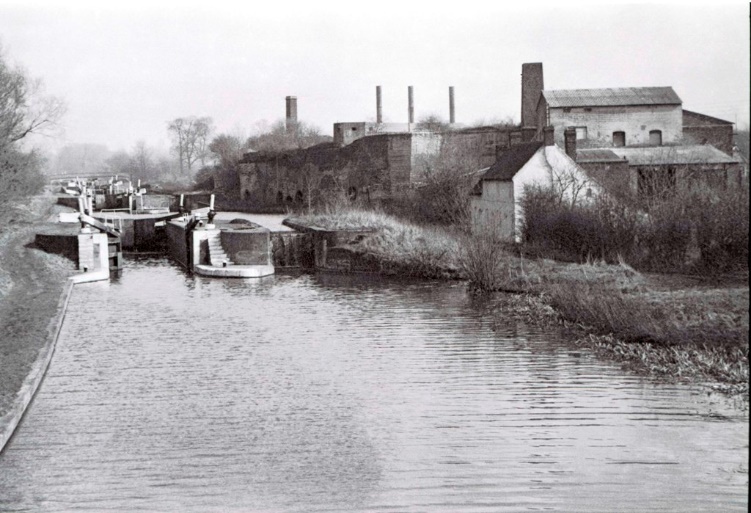

All three works were rail connected, with Southam and Stockton also having a canal wharf. In fact Southam continued to send cement to their Birmingham depot by canal until the Arctic winter of 1963 drove the final nail into the coffin of canal transport.

The rail connections took out cement products and brought in coal from the North Warwickshire pits and in the case of the Southam works, also a daily trainload of chalk from Bedfordshire which was part of the recipe mix.

When the Oxford & Wolverhampton (later Great Western Railway) opened in 1852, the new Harbury works was constructed by it to ensure rail access for incoming coal and outgoing product. This was ‘Greaves, Bull & Lakin’ and the GWR signal box controlling the rail access to the Harbury works was Greaves Signal Box for the whole of its existence.

Where Did the Cement Go

If a North to South line were to be drawn through Southam the bulk of deliveries went to the left, in other words an arc through Stoke-on-Trent to Shrewsbury, to Hereford and down to Bristol. This encompassed Birmingham and The Black Country and the overspill towns of the 1960’s, predominately Kidderminster and Worcester. There were exceptions to this when major one-off contracts came along as in Drakelow Power Station near Burton-on-Trent, the new runways at R.A.F. Benson for the Royal Flight, the Chichester by-pass and the M5 motorway.

The Families

Nearly all the families in the immediate area had someone working in the cement industry. I had an uncle at Stockton, another at Southam and my father at Harbury. I also had a spell at Southam first and then Harbury and this was replicated all around in other families. This produced a very classless society which is being eroded with time, it created a town where everyone knew each other and no introductions were necessary.

The Quarries

Today all three works have virtually disappeared, with the exception of the Southam chimney and some quarrying along the Southam to Rugby Road, to be expanded on over the next few years. However the earlier scars left by the quarrying will last forever.

‘Blue Circle’ quarried all the way from Ufton village to Bishops Itchington village, with additional pits at Lighthorne and Ardley in Oxfordshire. The Ufton quarry, though quite shallow, reached right up to Ufton village just short of the allotments and has resulted in much of the 100 acres of the Ufton Fields Nature Reserve.

There was a narrow gauge railway from there down to the stone washery which was located down the concrete road coming out by the Deppers Bridge railway bridge near the Great Western Hotel. All the land where the Ufton Tip is now was quarry and evidence can still be seen near the tip entrance, where rush type marsh plants grow due to the disturbance of the water table. This is at the rear of what in 2016 is Codemasters.

The washery, operated by George Rathbone, was where great drying lakes of muddy water were released to evaporate. From the washery the clean stone was trucked up the concrete road and along the Bishops Itchington Road into the works. This was done in a large AEC Mammoth Major tipper lorry which was driven by “Lofty” McGreevy a very congenial (short) Irishman who lodged with Mrs Tomlinson in Daventry Street, Southam.

The deep Blue Lias quarry was to the right of the Bishops Itchington road (Bishops Bowl Lakes and Fishery) and again had its own railway system, the train being driven for some time by Bertie Holder of Southam who was another great local character, who operated donkey cart rides at local fetes. This line passed under the road in a tunnel on its route to the works.

In 1927 and 1928 there was again considerable local as well as national excitement surrounding the unearthing of an Ichthyosaur followed by a Plesiosaur fossilised skeleton in the deep Bishops Itchington quarry, both now being at the Natural History Museum in London along with the earlier Stockton fossil.

Further on, to the left was more quarrying almost right to the edge of the village and also the great spoil heaps fed by a continuous bucket chain.

When the shallow Ufton limestone seam ran out, ‘Blue Circle’ continued quarrying near Lighthorne and then Ardley which is near the Cherwell Valley Services on the M40. This latter stone was then brought to Harbury works by train. I think the need was to mix a lighter limestone with the dark Blue Lias to achieve the required mix.

Rugby Cement and the Stockton quarries worked towards each other reaching from the old Stockton Station to the very edge of Long Itchington village.

A Legacy

A pleasant aside to finish with, is that in 1937 a Manchester company was contracted to install a new kiln at Southam works. Four of the Manchester men that arrived met and married young Southam ladies, settled in the town, had families and lived out their lives here. Today three sons and one daughter of those unions still live in Southam all contributing in their own ways to the continuity of the big “cement family” still around.

Robert Sherriff

Excellent local history story. Much enjoyed reading about it.

Very fascinating, especially about the dinosaur skeletons – where are they now? I was interested in the Kay-lister family and found a lot more. J James

Both the Plesiosaur and Ichthyosaur skeletons were sent to the Natural History Museum in London.

My great uncle and second cousin worked at the cement works. George Taylor was a forman and supervised blasting. His son Albert I believed worked their too.

Very interesting. My great grandfather was Frank Johnson the works manager. The family once lived at The Grey House in Long Itchington.

My great grandfather was Frederick Richard Morgan marries Florence Harriett Gough in 1910 and was quarry man according to his marriage certificate. They Lived in the mansion house in bishops itching ton for a while. Does anyone have pics if they knew him? Fab stories to read. Just fascinating

We do have some records of other Morgans from Southam but not the names you mention I’m afraid. However you might like to try looking at the Memories of Bishops Itchington Facebook page if your Grandfather lived there – they often post old photos on their page and some of the people contributing to the page may be able to help you.

do you have information on the civl defence using the nelson works for training in the sixties

I’m afraid that I have never heard of the Civil Defence using Nelson’s Works, although it is entirely possible. After WWII it was closed as a production unit, with production carrying on at Southam Works – the ex-Kaye’s Works.

With the remaining structures becoming unsafe, the Royal Engineers were invited to use it to practice demolition work and they effectively brought it to the ground. The exact date for this is unknown at present but it is thought to have been in 1968. Seeing that Rugby Cement had contacted the army for that, it is quite possible that they would have been sympathetic to any earlier [or later?] use by the the CD.

There is a still a WWII air-raid shelter in the woods adjacent to the works, and that also would have given the CD something to exercise ‘evacuating’ casualties from.

It might be worth contacting the Stockton News [ http://www.stockton-warks-pc.gov.uk/community/stockton-parish-council-13233/stocktons-news/] as the editors always have interest in the old works, and a note or query there [if it is operating in these difficult times], may produce a memory from the more senior residents.

I should be very interested if you find anything. I remember as an army cadet in the early 1960s acting as a casualty for CD exercises at their training ground at Kidlington, Oxford – interesting, but frustrating if one was merely trapped and not an urgent case, so had to remain pinned in the ruins for hours!

I wish you well in your research, and look forward to any results.

My best wishes,

John Frearson

Hon Archivist, Rugby Portland Cement

Just tracing my family tree. Family name Hodges we know very little about them. From what I am finding out they worked in a quarry. if anyone as any images or information I would be grateful. They lived in Southam and the surrounding area.

Trying to build up a picture of their working lives.

I was near Nelson’s Wharf yesterday and impressed by the remains of several ‘kilns’ along their canal spur. heWn were these in use and how was their loading organised? I have a photograph but can’t see how to attach it here ! Hugh

Unfortunately this email address doesn’t seem to be accepting replies.

I’ve just come across your website. My grandfather Edward Badger, lived in Southam and worked in the .quarry. Unfortunately he diesd from silicosis, when my mum, Kathleen and her sister Gladys were about 17 years old. Other than that I know very little about him, I guess he might have been in one of the photographs of the quarry workers..

Thanks for your comment Jo. I know you said you know very little about your grandfather but is there anything you would like us to add to our records, even if it might seem insignificant? Sometimes quite innocuous things lead on to bigger discoveries.