Southam in the coaching era

Before the arrival of the railway, Britain had the  fastest and most efficient form of public overland transport the world had ever seen. The age of the stage coach in the early years of the 19th century was something of a golden age in long distance travel but it was short lived. As the railway spread across the land, coach travel underwent a rapid and terminal decline. Almost two centuries later, the only reminders are a few snowy Christmas card images of stage coaches.

fastest and most efficient form of public overland transport the world had ever seen. The age of the stage coach in the early years of the 19th century was something of a golden age in long distance travel but it was short lived. As the railway spread across the land, coach travel underwent a rapid and terminal decline. Almost two centuries later, the only reminders are a few snowy Christmas card images of stage coaches.

The coaching business

As the name suggests, the stage coach completed its advertised journey in a number of stages and at the end of each stage, the four horses would be changed at a roadside inn for a fresh team which then drew the coach for the next stage after which they would  be similarly exchanged. The average length of a stage was generally from eight to ten miles depending on the terrain. On some of the busier routes, the inns would require stabling for several dozen horses and accommodation for grooms, ostlers and others involved in the coaching trade. They also provided food and lodgings for passengers who were changing coaches.

be similarly exchanged. The average length of a stage was generally from eight to ten miles depending on the terrain. On some of the busier routes, the inns would require stabling for several dozen horses and accommodation for grooms, ostlers and others involved in the coaching trade. They also provided food and lodgings for passengers who were changing coaches.

To maintain a regular timetable, for the Birmingham to London route, of about a hundred miles, would require at least four coaches – an ‘up’ and a ‘down’ coach plus a spare vehicle at either end in case of breakdown. Reference to the Birmingham Tally Ho coach which came through Southam did not imply a single vehicle but rather any of the coaches that ran on the route. Each coach would be driven by a coachman and he generally had a guard who sat at the rear of the coach with his brass horn. Coaches were designed to carry a dozen or more people including the coachman and guard. Four of the paying passengers would travel inside the coach and the others would be seated on the roof exposed to the elements. The inside passengers paid twice as much as those seated on top.

Why Southam?

Most of the long distance coaches were owned and maintained by coach-builders who hired them out to the operators on a mileage basis. Outside London and on the shorter routes, many of the stage coach owners were inn keepers and landowners all of whom had a vested interest in the coaching business. Locally the owners of the Bath and The Royal hotels in Leamington, John Russell and Michael Copps were coach proprietors as also was Preston Mash who owned the Craven Arms hotel in Southam. They also owned many of the horses along with members of the local farming fraternity.

It is entirely due to its central location that Southam became a stopping-off place for the stage coaches. Situated on both a major North/South route from Coventry to Banbury and the equally important East/West route between Daventry and Warwick, it was also by coincidence exactly the right distance from each of those towns to be a changeover place for the horses pulling cross-country stage coaches.

Kings of the road

In 1820 there was a significant development in the  coaching business which in a few short years would come to be looked on as a national institution. A system of special coaches of a uniform design was introduced and operated under contract to the Post Office to carry mail to all parts of the kingdom. The Royal Mail was born and their prestigious vehicles became the epitome of transport by road. The standard pattern mail-coach was painted in formal dark red and black with scarlet wheels. The horses and driver were provided by the contractor but all of the guards were employed by the Post Office and were decked out in impressive style with top hats and uniforms of scarlet, frogged with gold lace.

coaching business which in a few short years would come to be looked on as a national institution. A system of special coaches of a uniform design was introduced and operated under contract to the Post Office to carry mail to all parts of the kingdom. The Royal Mail was born and their prestigious vehicles became the epitome of transport by road. The standard pattern mail-coach was painted in formal dark red and black with scarlet wheels. The horses and driver were provided by the contractor but all of the guards were employed by the Post Office and were decked out in impressive style with top hats and uniforms of scarlet, frogged with gold lace.

To safeguard the mail and any valuables that might be carried, the guard had a veritable armoury which included a blunderbuss, a cutlass and a pair of pistols. It was his responsibility to ensure that the mail-coach kept time and to that end he also had a sealed time piece which could only be unlocked when the coach arrived at its destination. This was of course in the days before Greenwich Mean Time had been introduced. Mail-coaches did not pay dues nor did they stop at tollgates and all other users of the road were required to give way to them. They were in short, very fast and since they also conveyed paying customers they became very popular. The one fundamental difference with the mail-coach was that they ran through the night with a whale-oil lamp on either side of the coach to illuminate the roadway.

To safeguard the mail and any valuables that might be carried, the guard had a veritable armoury which included a blunderbuss, a cutlass and a pair of pistols. It was his responsibility to ensure that the mail-coach kept time and to that end he also had a sealed time piece which could only be unlocked when the coach arrived at its destination. This was of course in the days before Greenwich Mean Time had been introduced. Mail-coaches did not pay dues nor did they stop at tollgates and all other users of the road were required to give way to them. They were in short, very fast and since they also conveyed paying customers they became very popular. The one fundamental difference with the mail-coach was that they ran through the night with a whale-oil lamp on either side of the coach to illuminate the roadway.

Southam’s coaching inns

The Craven Arms on Market Hill was the principal coaching inn at the turn of the 18th/19th century and  was owned in 1812 by Preston Mash a native of Lutterworth in Leicestershire. In 1829 his brother John Mash took space in the Leamington Courier newspaper to announce that he had bought The Craven Arms Posting Inn and Commercial Hotel and had taken over the premises from his brother. He also used the advert to include a reference to ‘coaches daily to all parts of the Kingdom’. The other documented coaching inn was only a few yards from the Craven Arms at the top of Oxford Street. This started out under the name of the New Inn run by John Bodily but within a short space of time had been renamed the Kings Arms which John Bodily no doubt thought had more of a ring to it than the New Inn which might have been viewed as having little history or pedigree.

was owned in 1812 by Preston Mash a native of Lutterworth in Leicestershire. In 1829 his brother John Mash took space in the Leamington Courier newspaper to announce that he had bought The Craven Arms Posting Inn and Commercial Hotel and had taken over the premises from his brother. He also used the advert to include a reference to ‘coaches daily to all parts of the Kingdom’. The other documented coaching inn was only a few yards from the Craven Arms at the top of Oxford Street. This started out under the name of the New Inn run by John Bodily but within a short space of time had been renamed the Kings Arms which John Bodily no doubt thought had more of a ring to it than the New Inn which might have been viewed as having little history or pedigree.

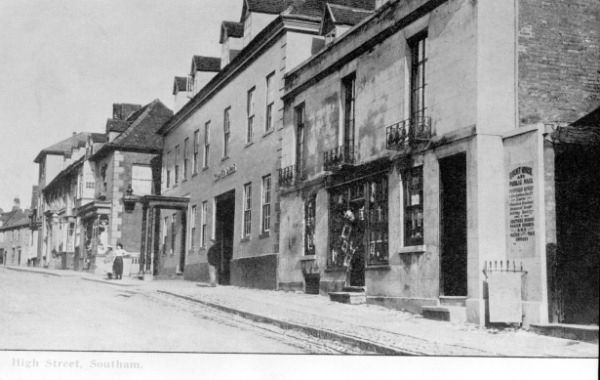

The Craven Arms had a large area of stabling for 80 or more horses at the rear of the inn. The Kings Arms formed part of a terrace and the stabling there backed onto the river and was entered through a gateway lower down the street next to the old police station. It has been suggested that the Bull in Daventry Street was also a coaching inn but I have seen no evidence of this, the Bull inn doesn’t appear in any contemporary newspaper advertisements for coaching or indeed in any of the trade directories of the period which list coaching inns.

horses at the rear of the inn. The Kings Arms formed part of a terrace and the stabling there backed onto the river and was entered through a gateway lower down the street next to the old police station. It has been suggested that the Bull in Daventry Street was also a coaching inn but I have seen no evidence of this, the Bull inn doesn’t appear in any contemporary newspaper advertisements for coaching or indeed in any of the trade directories of the period which list coaching inns.

Each day a dozen or more coaches changed teams in Southam en route for destinations to London or Liverpool and from Cambridge to Shrewsbury. Coaches leaving Southam for the capital would take one  of two quite separate routes depending on who the operator of the service was. The Sovereign ran on the Banbury – Bicester – Aylesbury route to the King’s Arms in Snow Hill but The Nimrod and The Express operated via Daventry – Towcester – Dunstable to the Old Bell, Holborn in the case of the Nimrod or to the Saracen’s Head, Snowhill in the case of The Sovereign. The Sovereign was one of the most popular services to London and was part-owned by John Russell of the Bath Hotel in Leamington and driven by Ben Ward, a Leamington man. It was advertised as ‘the only London coach that started from and ended in Leamington’. The ‘up’ coach to London arrived in Southam at 9.30 AM each morning and the returning ‘down’ coach arrived at 7.00 PM but not all of the coaches passed through at such social hours. The Express en route from London to Liverpool in 26 hours clattered into the Craven Arms yard at three o’clock in the morning. The Royal Mail out of London operated by J Hearn & co. bound for Stourport, arrived each morning just before 5.00 AM with post horn sounding to ensure the relief horses were harnessed up and ready to be put to.

of two quite separate routes depending on who the operator of the service was. The Sovereign ran on the Banbury – Bicester – Aylesbury route to the King’s Arms in Snow Hill but The Nimrod and The Express operated via Daventry – Towcester – Dunstable to the Old Bell, Holborn in the case of the Nimrod or to the Saracen’s Head, Snowhill in the case of The Sovereign. The Sovereign was one of the most popular services to London and was part-owned by John Russell of the Bath Hotel in Leamington and driven by Ben Ward, a Leamington man. It was advertised as ‘the only London coach that started from and ended in Leamington’. The ‘up’ coach to London arrived in Southam at 9.30 AM each morning and the returning ‘down’ coach arrived at 7.00 PM but not all of the coaches passed through at such social hours. The Express en route from London to Liverpool in 26 hours clattered into the Craven Arms yard at three o’clock in the morning. The Royal Mail out of London operated by J Hearn & co. bound for Stourport, arrived each morning just before 5.00 AM with post horn sounding to ensure the relief horses were harnessed up and ready to be put to.

The end of the road

For much of the coaching era there was great local competition for customers between the two principal Leamington coaching inns the Bath Hotel and Copp’s Royal Hotel. The Courier sold a lot of advertising space to these two establishments who engaged in a fierce price-cutting exercise frequently having their adverts side by side in the paper. The lowest fares on offer for the ten hour journey to London were inside 21 s and outside 10 s but the trade was rapidly diminishing.

If it can be said that if there was ever a ‘golden age’ for Southam, it must surely have been the three decades starting in 1800 when the stage coaches were in their pomp and brought both excitement and employment in their wake and put Southam quite literally on the map. By the end of the 1830’s it was becoming clear that future land transport would be steam driven rather than horse drawn and the coming of the railways finally put paid to what had been a colourful interlude in British history.

Alan Griffin March 2016

Sources:

- History of Southam & District – 4th Edition. J F Cardall Privately published. 1944

- Glimpses of our Local Past. – J C Manning. Frank Glover. Courier. 1895

- The Mail-Coach Men of the late eighteenth century. – Edmund Vale. David & Charles. 1967

- Directory of Stage Coach Services 1836. – Alan Bates. David & Charles. 1969

- The Coaching Age. – David Mountfield. Robert Hale & Co. 1976

- Stage & Mail Coaches. – David Mountfield. Shire Publications. 2003.

All images are from the author’s own archive